Drilling holes is one the most essential engineering tasks, the following details my techniques for sharpening drills and drilling hard metals.

Drills: types

Drills: types

High carbon steel—affected by heat and useless for hard metals, cheap and used for soft materials e.g. wood aluminium etc..

HSS—easily sharpened

Tin—HSS coated with titanium nitride the main purposes of using this is to draw heat from the tip and provide a sur-face which prevents metal sticking or catching on the drill. When the drill requires sharpening this coating is re-moved from the flanks , I would suggest the advantages are not worth it, just use a good quality HSS drill and use plenty of WD 40 as both a coolant to preserve the drill and a lubricant.

HSS Co—These drills are the preferred choice for hard metals, they are sharpened using diamond disc or fine sili-cone carbide at high speed.

HSSCo spiralux have an increased rake angle for stainless steels.

Tungsten carbide tipped—mainly used for drilling masonry however are now becoming available as twist drills for hard metals. requires a diamond disc to sharpen due to the hardness of this material.

Carbide micro grain—The Ultimate and expensive for hard metals and longer life

Sharpening

- Trueness: Place the drill into a chuck, rotate and check for trueness if bent discard the drill. It may of developed a crack.

- Visual: Check the drill: visually check for any damage, chipped off ma-terial, barbs on the shank must be removed, if there are any excessive wear on the flutes the drill will need to ground down.

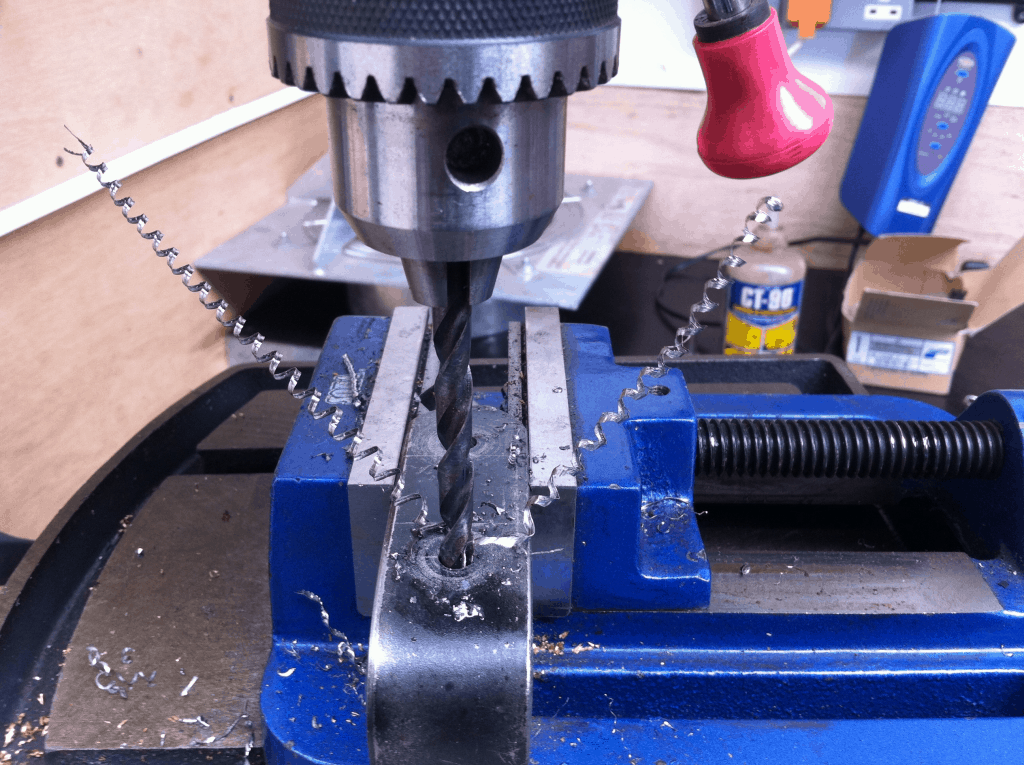

- Use of Grinders A grinder is useful to initially grind and shape the drill in preparation for final sharpening, The preferred method for final sharpening of drills for use with hard metals is the abrasive moving off the cutting edge of the drill bit. A grinder only allows the drill to be sharpened with the abrasive coming onto the cutting edge. In addition the abrasive on a fine grind wheel is still too coarse for finishing and pro-duces a serrated cutting edge, this is undesirable as the cutting edge will cut unevenly producing : more heat , as the peaks of the cutting edge will wear before the dips, will need re-sharpening more often . The swarf will not spiral off the drill and workpiece as desired. see picture .

The cutting edge must be as smooth as possible.

4, Point angle a drill is so designed so that at 118 degrees the cutting edge is straight, this accuracy is difficult to achieve by eye however an angle close to this can be achieved with practice.

Balance Both cutting edges must be balanced or the resultant drilled hole will be oversized. When sharpening contin-ually rotate 180 and compare and match the length of each cutting edge. - Final sharpening : The preferred method to final sharpen a drill without professional equipment is to use a dremel or similar with a either a fine silicone carbide grinding disc or a fine diamond Set to highest speed using the abrasive off or along the cutting edge, never on. This produces the desired polished smooth finish to the cutting edge.

When sharpening avoid producing any heat, heat is detrimental and will destroy the hardness of the drill. Diamond discs produce less heat. - The clearance angle, ignore the rule of 7 to 10 degrees, this angle is too acute and can cause the drill bit to judder where the cutting edge digs in and jumps out of the workpiece, this angle should be kept to a minimum, sharpening to these fine toler-ances can be developed using practice, trial and error.

Small drills < 3 mm General advice is to discard these drills when blunt as they are difficult to sharpen. I recommend using small drills of the highest quality as achieving the initial pilot hole is important as it guides the main drill. With practice these can be sharpened, close up safety glasses and good lighting are essential.

A word on Dremel type rotary drills

Sharpening in the field: No matter what material you are drilling will require sharp drill bits and these will become dull in use . A simple check is to observe the cutting edge closely and rotate the drill, if you can see a glint of reflective light from the cutting edge. the drill is blunt. To resharpen in the field or in the workshop I recommend a dremel or a dremel equivalent for its portability and the very high speeds using either silicone carbide or even better a fine diamond disc.

Diamond discs are now cheap and available for dremels or similar unfortunately they do have drawbacks the discs them selves are excellent and are able to sharpen without creating too much heat, however the arbour interface to the drill has shortcomings which have been overcome with the anti flex diamond disc adaptor

Disc flexing: The disc requires a backing pad robustly connected to the adaptor to reduce flexing in use, should be made in a light material such as aluminium and must be balanced to prevent wobble .

Disc Slipping the standard screw and arbour are prone to slipping a backing pad ensures the disc grips by utilising the friction created between the diamond abrasive to soft metal back.

When sharpening, it is desirable that the cutting edge is made safe. This is achieved by making the backing pad slightly larger in diameter that the disc.

The 4 facet sharpening technique

This method has the following advantages

- when mastered can produce a more accurately balanced cutting edge.

- The clearance angle is easier to produce, a minimum clearance angle is preferred to avoid the tip digging into the work piece and chipping the drill, as it attempts to remove too much material at once.

- The web or core thickness is reduced, occasionally this avoids having to use a pilot drill .

- when mastered reduces sharpening times, on occasion cutting edge only requires slight redressing